The following was written by Y.M. Saegusa an Advocate for regenerative agriculture and environmentally sustainable living. Future homestead owner. Editor of https://medium.com/satoyama AND borrowed from this site https://ymsaegusa.medium.com/

Our Soil is Dying…, What Can We Do About It?

Soil is one of the least understood but most important requirements for sustainable agriculture

Soil is living. Soil contains living organisms such as worms, fungi, insects, and other organic matter.

A single handful of healthy soil contains more than 50 billion life forms. To put things in perspective, the global population currently sits at about 7.8 billion. Taking it one step further, approximately 117 billion humans were ever born. That means a little over two handfuls of healthy soil can contain more life forms than all humans that ever existed.

The life forms contained within soil, nutrients, and minerals all help plants grow healthier and nutrient-rich while increasing crop yield.

Topsoil is required to support 95% of our global nutritional requirements. This not only includes the crops that we eat but the plants that are fed to livestock. Without healthy soil, we are screwed.

Healthy soil also acts like a sponge, which absorbs and retains water. Soil free of chemicals and synthetic materials enables the water to reach the underground aquifer to replenish it without contaminating it.

Plants use carbon dioxide for photosynthesis. The carbon captured during this process is stored in the soil. When soil degrades, carbon is released back into the atmosphere. Just within the European Union countries, approximately 75 billion tons of carbon is stored in the soil. When soil erodes, the carbon that is sequestered within the soil is released back into the atmosphere.

But our soil is dying…

The impact of industrial agriculture on soil health

According to some estimates, we’ve lost nearly half of productive topsoil in the last 150 years. Industrial-scale agriculture has contributed to the loss of naturally productive soil through unsustainable agricultural practices that are damaging to the soil and the environment.

One of which is monocropping, or the agricultural practice of growing the same crop over and over on the same plot of land. At the industrial scale, it’s efficient, maximizes crop yield, and returns higher revenues. Specializing at the industrial scale results in a farm that is easier to manage and costs less to operate. But does its benefits outweigh the impacts?

Growing crops this way results in depletion of the soil’s nutrients and reduces the level of organic matter in the soil. Monocropping yields may also decrease over time due to the soil being depleted of vital nutrients. Because plants require nutrients to grow, farmers must make up for deficiencies by applying chemical fertilizer.

Because only a single species is planted in a concentrated area, the plants are susceptible to pest predation and diseases, which are controlled using chemicals. Bactericides, fungicides, nematicides are all be applied to crops at various stages of growth to control diseases. Pesticides are also used to control insects.

During the off-season after harvest, the soil is left bare without a cover crop to hold the soil, contributing to soil erosion. With no roots to keep soil in place, soil can be lost due to wind or rain run-off.

The advancement of technology also means farmers can plant genetically modified crops. These crops are modified so that they are resistant to specifically formulated herbicides and pesticides. Farmers can spray the field to control insects and weeds without killing the crops. This practice destroys naturally beneficial organisms in the soil, which must be offset by applying synthetic fertilizers to replace the nutrients in the soil which plants require. Weeds and native plants which can control erosion are also killed by herbicides.

Remember this simple formula:

Soil is alive. Dirt is dead. You cannot grow plants in dirt. Dirt does not contain any nutrients, minerals, or organic matter that are found in soil and is required to sustain plant life. Dirt does not support life on its own.

Monocropping, heavy use of chemical fertilizers, and chemical pesticides kill the soil gradually. Poor land management, extensive plowing and tilling, and replacing native plants with cash crops; all of these agricultural practices remove the vast network of roots and organic matter that keep soil healthy and moist, which prevents erosion.

The ground which is infused with various synthetic fertilizers and chemicals also puts at risk the groundwater. The same water that is used to water the crops.

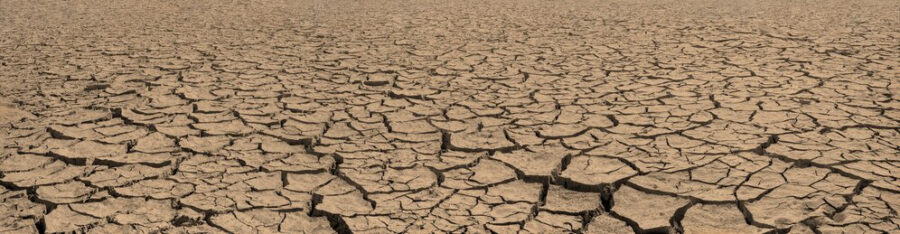

What happens when you combine poor land management, dying soil, and extended bout of droughts (regardless of cause)? This:

There is precedence to all of this. Our country has been through it before. Let’s not go through it again.

What can we do about it?

There are alarming articles that can be found throughout the internet that claims there are only 60 years of topsoil left if current industrial agricultural practices are sustained. Anything found on the internet needs to be thoroughly questioned to ensure the veracity of the information before its accepted as fact.

But here is a fact. We have to feed the world. I care about the environment but I am also pragmatic. My family does its best to consume organic foods as much as possible, but some of what we eat are GMO or GMO derived. Organic food is expensive. It’s a luxury.

But we can grow our food without killing the soil. For farmers and homesteaders that choose to engage in sustainable agricultural techniques, there are options.

On-site composting to produce organic fertilizer is one option. We can control what goes into our compost pile, so we know that our fertilizer is 100% organic and natural. This compost can be applied to the soil to restore its health. Healthy soil does a better job at retaining moisture and produces healthier crops that are completely natural. Foliage and other bio-products generated by the farm can be fed back into the compost, making it sustainable.

Planting cover crops and using mulch on the field will help reduce soil erosion and runoff. Cover crops also reduce the impact of soil compaction, so that the soil actually absorbs and retains moisture.

We can minimize tilling and plowing because it kills the soil and the root structures that are holding it in place. These roots and fungi sequester carbon, which is released when the soil is disturbed needlessly.

We can plant insectary plants to create an eco-sphere that is inviting to beneficial insects. Insects like ladybugs, praying mantis, and even spiders all help mitigate the population of pests.

We can incorporate farm animals will also restore soil health. Some animals like fowls (duck, goose, chicken, etc.) can be used to control pests while producing manure and urine that naturally fertilizes the soil. Larger animals can help control weed and also produce manure and urine.

We can support local organic farmers by becoming a member of your local Community Supported Agriculture (CSA — Link *not* an affiliate or advertisement) is also an option. My family is a member, and we receive a weekly box of organically grown produce from a local farm. Some CSAs may also provide organic meats and animal products as well. Our CSA offers tours and educational outreach (pre-Covid) along with recipes for uncommon and unique produce. And you are supporting a local farmer that engages in sustainable practices for farming.

For those who are not farmers and/or have no aspirations of homesteading as my family does, then being informed is a good first step. Know where your food comes from. By being informed, you can decide what you want to do with that knowledge.

Why is soil conservation important?

borrowed from https://geopard.tech/blog/why-is-soil-conservation-important/

Soil offers the firmament on which we live and develop. It gives nutrients to trees, plants, crops, animals, and a hundred million microorganisms, all of which are required for life to continue on Earth. If the soil becomes unsuitable or unstable, the entire process comes to a halt; nothing else can grow or break down. To avoid this, we must be aware of the beautiful ecosystem that exists beneath our feet. But what exactly is soil conservation, and how can we become involved?

What is soil conservation?

Soil contains nutrients that are necessary for plant growth, animal life, and millions of microorganisms. The life cycle, however, comes to a halt if the soil becomes unhealthy, unstable, or polluted. Soil conservation is concerned with keeping soils healthy through a variety of methods and techniques. Individuals who are committed to soil conservation assist to keep the soil fertile and productive while also protecting it from erosion and degradation.

Why is soil conservation important?

Conservation cropping systems rely heavily on soil conservation. There are numerous advantages for producers who opt to use soil conservation methods on their farms.

Profit Enhancement:

- Yields are comparable to or higher than traditional tillage.

- Cut down on the amount of fuel and labor used.

- It requires less time.

- Lowering the cost of machinery repair and maintenance.

- Potential cost savings on fertilizer and herbicides.

Improved Environment:

- Increased soil productivity and quality.

- Less erosion.

- Increased infiltration and storage of water.

- Better air and water quality.

- Offers food and shelter to wildlife.

Soil Formation Factors

- Parent material refers to the rocks and deposits that formed the soil.

- The climate in which the soils formed.

- Living organisms that altered soils.

- The land’s topography or slope.

- The geological time span during which the soils have evolved (age of the soil).

Ten good reasons to practice soil conservation

The following are the top 10 reasons:

- Soil is not a renewable natural resource. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), forming a centimeter of soil might take hundreds to thousands of years. However, erosion can cause a single centimeter of soil to be lost in a single year.

- To maintain a steady supply of food at economical rates. Soil conservation has been shown to boost agricultural output quality and quantity over time by retaining topsoil and preserving the soil’s long-term productivity.

- Soil serves as the basis for our structures, roads, homes, and schools. In truth, the soil has an impact on how structures are constructed.

- Beneficial soil microbes live in soils; these creatures are nature’s unseen helpers. They develop synergistic interactions with plants, among other things, to protect them from stress and nourish them with nutrients.

- Soils remove dust, chemicals, and other impurities from surface water. This is why underground water is one of the purest water sources.

- Farmers benefit from healthier soils because they increase agricultural yields and protect plants from stress.

- To enhance wildlife habitat. Soil conservation methods such as establishing buffer strips and windbreaks, as well as restoring soil organic matter, considerably improve the quality of the environment for all types of animals.

- For purely aesthetic grounds. To make the scenery more appealing and gorgeous.

- To contribute to the creation of a pollution-free environment in which we can live safely.

- For our children’s future, so that they will have adequate soil to support life. According to legend, the land was not so much given to us by our forefathers as it was borrowed from our children.

Soil conservations practices

There are a variety of useful soil conservation measures available, some of which humans have used since the dawn of time. The following are some of the most common examples of such practices:

Conservation tillage

Conservation tillage is an agro management method that seeks to reduce the intensity or frequency of tillage operations in order to realize both environmental and economic benefits.

Conventional tillage refers to the traditional way of farming in which soil is prepared for planting by thoroughly inverting it with a tractor-pulled plow, followed by tilting further in order to level the surface of the soil for crop cultivation. Conservation tillage, on the other hand, is a tillage approach that reduces plowing intensity while keeping crop residue to conserve soil, water, and energy resources. Planting, growing, and harvesting crops with as little disturbance to the surface of the soil as feasible is what conserved tillage entails.

Soil tillage promotes microbial decomposition of organic matter in the soil, resulting in CO2 emissions into the atmosphere. As a result, reducing tillage encourages carbon sequestration in the soil. Many crops can now be produced with minimal tillage thanks to advances in weed control technology and farm machinery over the previous few decades. There are several types of conservation tillage practices:

Conservation tillage necessitates the management of crop remains on the soil surface. Crop residues, a renewable resource, are important in conservation tillage. When crop residues are managed properly, they protect soil resources, improve soil quality, restore degraded ecosystems, improve nutrient cycling, increase water conservation and availability, enhance pest suppression, such as weed and nematode suppression, reduce runoff and off-site nutrient leaching, and sustain and improve crop productivity and profitability.

Conservation tillage can be used in conjunction with other measures to maximize the soil benefits of reduced tillage and increased soil-surface coverage.

Contour farming

Contour plowing lowers runoff while also assisting crops and soil in maintaining a steady altitude. It is accomplished by furrowing the land with contour lines between the crops. This strategy was used by the ancient Phoenicians and has been shown to retain more soil and enhance crop yields by 10% to 50%.

Strip cropping

Strip cropping is a farming technique used when a slope is too steep or too long, or when there is no other way to prevent soil erosion. It alternates strips of closely planted crops like hay, wheat, or other small grains with strips of row crops like maize, soybeans, cotton, or sugar beets. Strip cropping helps to prevent soil erosion by providing natural dams for water, thus preserving soil strength. Certain plant layers absorb minerals and water from the soil more efficiently than others. When water hits the weaker soil, which lacks the minerals required to strengthen it, it usually washes it away. When strips of soil are strong enough to restrict the flow of water through them, the weaker topsoil cannot wash away as easily as it would ordinarily. As a result, arable land remains fertile for much longer.

Windbreaks

Windbreaks are an excellent approach to reducing soil erosion in flat farming settings. This is made easier by planting rows of dense trees between the crops — evergreens are a wonderful year-round solution for this — or by planting crops in an unconventional fashion. Deciduous trees may also function if they can stand vigil all year.

Crop rotation

Crop rotation is a fantastic strategy to combat soil infertility and has been used with great success for as long as there have been crops to grow. Crop rotation is regarded as excellent practice in organic farming by the Rodale Institute. Crop rotation is the technique of cultivating a variety of crops in the same location over the course of a growing season. The nutritional requirements of various crops vary. Because the crops are rotated each season, the approach decreases reliance on a single source of nutrients.

Cover crops

Cover crops are an essential component of the stability of the conservation agriculture system, both for their direct and indirect effects on soil characteristics and for their ability to encourage enhanced biodiversity in the agro-ecosystem.

While commercial crops have a market value, cover crops are mostly produced for soil fertility or as fodder for livestock. Cover crops are beneficial in areas where less biomass is produced, such as semi-arid (dry) areas and eroded soils, because they:

- protect the soil during fallow periods

- mobilize and recycle nutrients

- enhance soil structure and break compacted layers as well as hardpans

- allow for rotation in a monoculture

- can be used to control pests, weeds, or break soil compactness

To make use of the moisture that is residual in the soil, cover crops are frequently grown during periods of fallow, such as the period between crop harvest and the next planting. Their growth is stopped before or after the next crop is planted, but prior to the rivalry between the two types of crops commences. Another excellent soil conservation method that reduces erosion from runoff water is the use of cover crops.

Buffer strips

Buffer strips are permanently vegetated zones that safeguard water quality between a canal and a farm field. Buffer strips to aid in soil retention by slowing and sifting storm flow. As a result, the amount of hazardous phosphorus that enters our lakes may be minimized.

A buffer strip begins at the edge of the water and extends at least 30 feet inward towards the land, providing aesthetic surroundings and habitat for wildlife. Buffers aid in the retention of soils and can also be used to grow plants that can be gathered and used as animal feed. Buffers exist in a variety of shapes and sizes, including:

- Harvestable buffer strips –These are crop buffers that can also be harvested later on for forage by farmers.

- Contour buffer strip – utilized in sloped agricultural areas to prevent erosion and limit downhill precipitation velocity.

- Shoreline gardens – a buffer between a manicured residential lawn and a lake

Benefits of buffers

- Less soil erosion – They aid in the retention of soil.

- Wildlife habitat – provides food and cover for wildlife.

- Protect and extend stream health – prevents loose silt from filling drainage ditches and streams.

- Streambank integrity – more vegetation stabilizes the stream bank

- Aesthetic appeal

Grassed waterways

Grassed waterways are shallow, broad, saucer-shaped pathways that carry surface water over fields without causing any erosion to the soil. The river’s plant cover tends to slow the flow of water and protects the channel surface from erosion forces induced by runoff water. If left alone, runoff and snowmelt water will drain into a field’s natural draws or drainage pathways.

Grassed waterways securely move water down natural draws through fields when appropriately scaled and created. Waterways also serve as outlets for terrace systems, contour cropping patterns, and diversion channels. When the watershed area generating the runoff water is quite big, grassed rivers are a good solution to soil erosion caused by concentrated water flows.

How it helps

- Grass cover protects the canal from gully erosion and captures sediment in runoff water.

- Vegetation can also filter and absorb some of the pollutants and nutrients in runoff water.

- Vegetation serves as a safe haven for little birds and animals.

Terrace

Terracing is an agricultural process that involves rearranging cropland or converting hills into agriculture by building particular ridged platforms. Terraces are the name given to these platforms.

Terrace farming is an efficient and, in many cases, the only solution for hilly farmlands. Terraces are a fantastic water and soil conservation structure to use if you have sloping fields in your operation to decrease soil erosion and conserve soil moisture on steep slopes. The types of terraces that can be employed (narrow-based, broad-based, or terrace channels) are adaptable to your demands and soil type, and they can be spaced based on erosion possibilities and equipment considerations.

Terraces play a significant role in minimizing soil erosion by delaying and lowering the energy of runoff. Some terraces collect drainage water and redirect it underground rather than overland as runoff. If erosion is a major problem on sloping terrain, one option to explore is a terrace system to slow and manage surface runoff and prevent soil erosion. Once created, a terrace, like any conservation technique, demands hands-on monitoring and upkeep to ensure peak effectiveness.

Drop inlets and rock chutes

A drop inlet, also known as a shaft spillway, is made up of a vertical intake pipe and a horizontal underground conduit pipe. Water enters the vertical pipe at ground level and descends below, where it is safely channeled through a massive concrete, metal, or plastic pipe into a spillway such as a stream or ditch.

A rock chute spillway is a construction that allows surface water to flow safely into an exit. This type of spillway aids in bank stabilization by reducing retrogressive erosion of waterway bottoms (furrows and ditches) and the production of erosional gullies in fields. This adaptable, low-cost, and effective construction is easily altered to the location and has minimal disadvantages for agricultural techniques. However, unlike a building with a sedimentation basin, it does not allow for water retention or the sedimentation of soil particles in runoff water. The rock chute spillway is used to alleviate erosion problems at the bottom of fields, at the outlet of a furrow, an interception channel, or a grassed waterway, or anywhere water flows into a stream.

Drop inlets and rock chutes are frequently used to “step” water down where there are abrupt elevation changes, thus protecting soil from erosion.

Livestock dung, mulch, municipal sewage, and legume plants such as alfalfa and clover are examples of natural fertilizers. Manure and sludge are put to the field by spreading it out and then kneading it into the soil. Timing applications must adhere to strict restrictions, as both sludge and manure can cause significant water contamination if managed improperly. Grown legumes like clover or alfalfa are subsequently tilled into the soil as “green fertilizer.”

Natural fertilizers, like chemical fertilizers, replenish the soil with important elements such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. They do, however, have the added benefit of contributing organic matter to the soil.

Bank stabilization

Bank stabilization refers to any technique used to keep soil in place on a bank or in a river. Here, the soil can be eroded by waves, stream currents, ice, and surface runoff.

Advantages of bank stabilization are decreased soil erosion, increased water quality, and a more aesthetically pleasing setting.

Gabion baskets, re-vegetation, and rip rap are three typical methods for controlling erosion at a stream or riverbank. The first two options rely on loose rock to preserve the underlying loose soil surface by cushioning the impact of stream water on the bank. The term “rip-rap” refers to loose rock on a steeply sloping bank. Riprap, on the other hand, can survive the rigors of ice and frost, whereas concrete may fracture. Gabion baskets are usually wire baskets filled with rocks. The wire baskets hold the rock in place. They are frequently used on steeper slopes and in regions where water flows quicker.

Planting along the shoreline might also help to stabilize stream banks. Shrubs, natural grasses, and trees slow the flow of water across the soil and trap silt, keeping it out of the water.

Organic or ecological growing

Organic farming is a farming practice that includes ecologically based pest treatments and biological fertilizers obtained mostly from animal and plant wastes, as well as nitrogen-fixing cover crops. Modern organic farming evolved in response to the environmental damage caused by the use of chemical pesticides and synthetic fertilizers in conventional agriculture, and it offers significant ecological benefits.

Organic farming, when compared to conventional agriculture, utilizes fewer pesticides, lowers soil erosion, reduces nitrate leaching into groundwater and surface water, and recycles animal feces back into the farm.

Sediment control

Similar to how agricultural soil erosion affects yields and plant growth, urban soil erosion reduces the possibility of healthy landscape plantings. This is especially true during urbanization when mass grading alters the natural soil profile and results in a large loss of topsoil.

When soil is subjected to the effects of rainfall, the volume and velocity of runoff increase. This causes a chain reaction that results in sediment movement and deposition, lower stream capacity, and, eventually, increased stream scour and floods.

Though temporary, erosion and sediment control methods safeguard water resources from sediment contamination and increases in flow caused by active land development and redevelopment activities. Sediment and related nutrients are kept from leaving disturbed regions and polluting waterways by keeping soil on-site.

Erosion control measures are primarily aimed to minimize soil particle detachment and transportation, whereas sediment control practices are designed to confine eroding soil on-site.

Integrated pest management

Pests are a huge nuisance for farmers and have been a major difficulty to deal with, while pesticides damage nature by leaking into the water and the atmosphere. It is critical to replace synthetic pesticides with organic ones wherever possible, to build biological enemies of pests whenever possible, to rotate crop types to avoid expanding insect populations in the same field for years and to use alternative strategies in complex situations.

Integrated pest management (IPM) employs a number of strategies aimed at reducing the usage of chemical pesticides and, as a result, environmental hazards. Crop rotation is the foundation of IPM. Pests are starved out and less likely to establish themselves in harmful numbers the next year when crops are rotated from year to year. Crop rotation has been shown to be an effective pest management approach.

To control pest populations, IPM also employs pest-resistant crops and biological measures such as the discharge of pest predators or parasites.

Although IPM takes more time, the benefits of soil conservation, a better environment and lower pesticide expenditures are undeniable.

Soil health by region

Farmers can utilize a range of measures to maintain the health of their soils. Some of these techniques include avoiding tilling the land, planting cover crops in between growing seasons, and switching the crop variety grown on each field.

According to a recent study, soil health information is commonly oversimplified. Farms don’t all yield the same outcomes. While one technique may be advantageous to one person, it may be problematic for another depending on where they live.

More specific trends in soil health are best observed and evaluated at the regional to the considerable diversity in landscape, inherent soil quality, and farming practices. Let’s take a look at soil specifics of Canadian provinces.

British Columbia

The need for soil protection varies substantially in British Columbia due to the wide range of cropping intensities. The greatest danger to soil conservation is posed by high-value specialty crops, as well as the heavy tillage and mechanical traffic that goes with them.

The bulk of BC’s agricultural land is under high to severe risk of water erosion when the soils are bare. In the Fraser Valley, this is due to heavy rainfall and some steep cultivated slopes; in the Peace River region, it is due to easily eroded silty soils and vast fields with lengthy slopes at the foot of which melted snow runoff collects and washes soil away. Conservation efforts, however, have considerably reduced these dangers over the previous several decades.

Prairie Provinces

Many arable soils on the plains and grasslands are subject to wind erosion and salinization as a result of the strains of a dry climate. Vulnerable soils are also prone to water erosion, especially following summer storms or spring runoff. Severe wind erosion prompted the establishment of the Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration in 1935, which took quick and extreme measures to address the problem. When wind erosion became more widespread, efforts were reintroduced to encourage the use of soil conservation practices from the mid-20th century onwards.

Improvements can be attributed to reduced use of summer fallow and increasing use of conservation tillage and other erosion controls, such as permanent grass cover and shelterbelts. The risk of soil salinity has decreased in some areas due to greater use of permanent vegetation cover and less frequent use of summer fallow.

Ontario and Québec

Crops such as corn and soybeans are abundantly cultivated in central Canada. These crops are planted early and harvested late because they require the longest growing season possible. The soil is frequently moist while these processes are carried out, resulting in the compaction of the soil. Moreover, these plants may lead to inadequate soil protection from rain and snowmelt erosion for prolonged periods of the year.

Soil conservation practices like minimum and no-tillage retain crop residues on the surface of the soil and reduce heavily loaded mechanical activity. Crop rotation and the regular use of clover or alfalfa hay crops increase soil organic matter, culminating in a better soil structure and less stress. Manure and an adequate amount of fertilizer have a similar impact. Seeding places where runoff water collects to generate grassed streams also helps to reduce soil erosion.

Wind erosion is rarely a problem, and it is usually restricted to locations where the soil is sandy or contains organic material (e.g., cultivated marshes). Windbreaks can be established in these sites by planting rows of trees or bushes, and agricultural leftovers can be retained on the surface of the ground to protect the soils from wind erosion.

Atlantic Canada

The soils in none of the four Atlantic Provinces are very productive. The soils are frequently depleted by nature and are often acidic. The intensive cultivation of vegetable crops and potatoes has further lowered organic matter levels, harmed soil structure, and resulted in severe soil erosion on sloping grounds.

Farmers are combating these concerns by utilizing soil conservation techniques. Terraces, which are regular canals created across hills, are becoming more popular in the potato-growing areas of New Brunswick. By decreasing the length of the slopes, the terraces limit runoff water buildup. They transport the water to the field’s edge. They also encourage farmers to plant crop rows across the slope rather than up and down the hill, which ultimately reduces soil erosion caused by runoff. Crop rotation is another method of soil conservation in which potatoes are planted alternately with cereal crops (such as clover and barley). Grassed rivers are also employed in regions where water pools naturally, decreasing the danger of erosion carving gullies through the soil. In this region, the usage of significant amounts of fertilizer for the potato crop frequently raises soil acidity. Farmers apply ground limestone to the soil and mix it using plowing tools to regulate soil acidity.

To Sum Up

Conserving soil is a major concern for individuals, farmers and businesses because it is critical not only to use land productively and provide high yields but also to be able to do so in the future. Even though the impacts of soil conservation might not be visible in the short term, they will be beneficial to future generations. By integrating various methods of pest and weed control, different ways of soil conservation help to prevent erosion, maintain fertility, avoid deterioration, as well as reduce natural pollution caused by chemicals. Therefore, soil conservation initiatives provide a great contribution to the long-term viability of the environment and its resources.